Hearing-centric design in video chat apps

May 20, 2020

Note: If you are not familiar with Deaf and hard of hearing (DHH) culture, I recommend reading Deaf 101 by the Hearing, Speech & Deaf Center (HSDC) first.

Introduction

Around mid-March, the COVID-19 pandemic started to really affect life here in Vancouver. Within the span of a few days, we went from business as usual to the shut-down of most of the city's public spaces.

This was a challenge for the ASL (American Sign Language) practice meetup I help organize, ASL Social and Practice. Up until this point, we had been meeting in person at a public library. For the health and safety of our participants, and since more and more potential venues were shutting down anyway, we decided to look at whether it'd be feasible to move our meetup online.

You might have expected that since sign languages are so visual, they would be well-suited for a visual format such as video. While video chat technology has made it possible to communicate in sign language online, it is no replacement for conversing in person. Since ASL is a 3-dimensional language, certain aspects of the language cannot be preserved in a 2-dimensional format.

With this in mind, three of us from the ASL practice group tested out the following video chat apps:

- Discord

- Google Hangouts

- Google Meet

- Houseparty

- Jitsi Meet

- Skype

- Zoom

As expected, we did experience more difficulties communicating in sign language through video than in person. For example, it was tricky to get a particular person's attention, which we typically do by waving towards them and making eye contact. It's just not possible on video since there's no way to position ourselves in relation to others (unless everyone's got their own MVPD, that is).

While some issues were unavoidable due to the nature of the video format, there were additional difficulties caused by the apps' designs. Like most things in the world, video chat apps were created for the hearing. If DHH had been considered while designing the app, these issues would not be so common.

For the remainder of this blog post, I will list and describe the designs commonly found in video chat apps that make it more difficult to communicate without relying on audio. It is important to note that most of these issues were discovered during ASL practice with mostly hearing participants, and are not a representation of the DHH experience. At the same time, it's clear that many of these design choices would have an impact on communication with signing, lip-reading, or when there are audio quality issues.

This isn't a comparison or critique of specific platforms, especially since these issues are so common. In case it's useful to know, though, we did end up settling on Jitsi Meet for now. Google Meet is quickly becoming a good contender with all the features they've been rolling out.

Designs

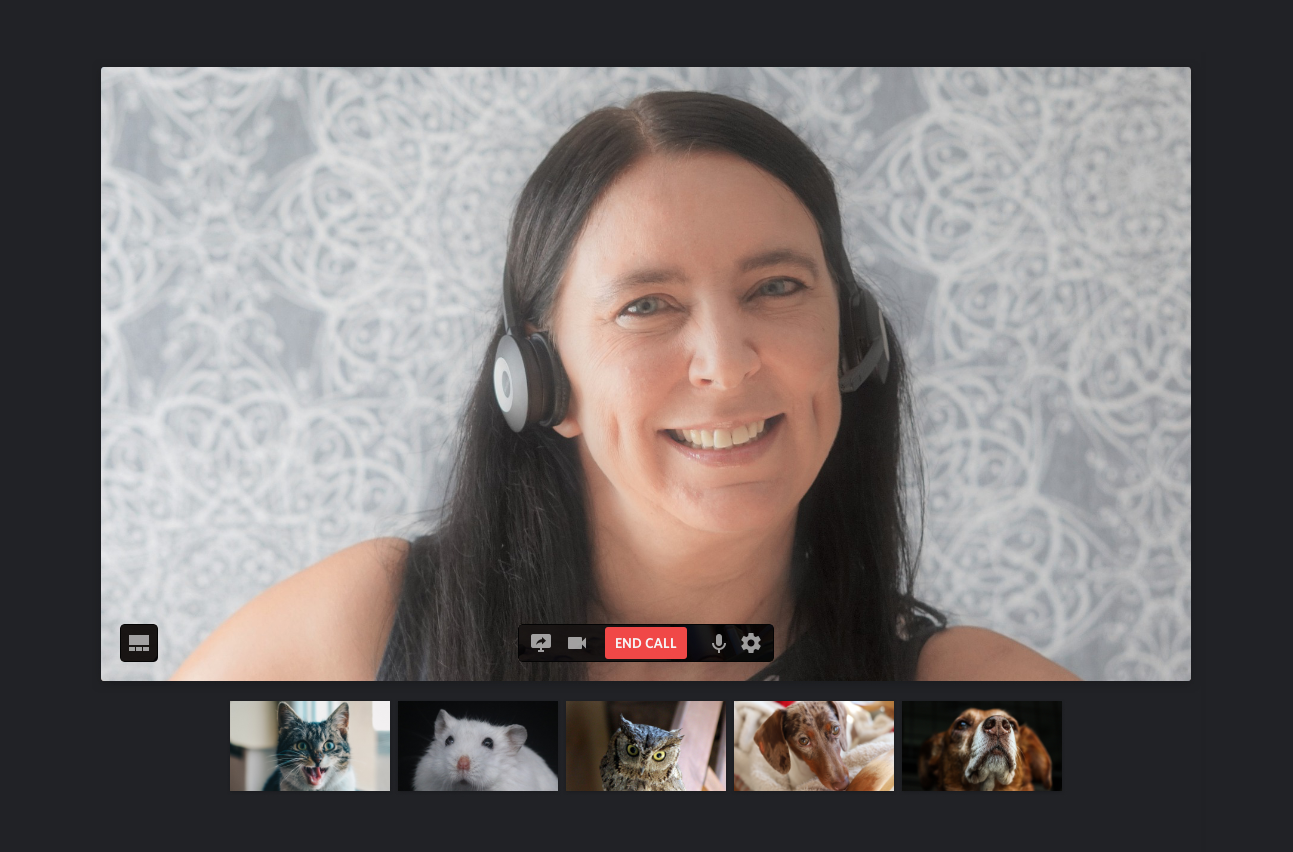

The one large featured video layout

There are a few issues with this very common video layout, which displays one featured video at a large size. In some variants of this layout, the featured video is all that's visible. In others, the other people's videos are shown at the same time but at a much smaller size. In both cases, more videos could be shown on the screen if the featured video weren't so large.

Featuring video based on audio

Typically, the featured video is selected based on who is making the most noise. This works so-so for speaking-hearing conversations, since participants can see and listen to the current speaker. It still doesn't work that well when more than one person is speaking at a time, or if there's background noise. When communicating in sign language, focusing on the person that is making the most noise might swap out someone that is actively signing for someone that is only watching and happens to be making more noise.

Videos too small to see details

Video dimensions don't have much of an effect on speaking-hearing conversations, since there is no impact on audio quality. However, if the videos are too small to clearly see hand shapes and facial expressions, it can make signing and lip-reading difficult or even impossible. If the app treated hearing-speaking conversations the same way, it would muffle everyone's microphones except for the one featured person's.

Hiding more videos than necessary

With a large group video chat, it makes sense to limit the number of videos shown at a time so they don't display at tiny sizes. In this layout, though, more videos could fit on one screen at reasonable sizes if the featured video didn't take up so much room. While there is a balance to maintain, there is no way to lip-read or receive signing from a hidden video. If the app treated hearing-speaking conversations the same way, it would mute everyone's microphones unless they were shown on-screen.

Not showing your own video

While some video chat apps show your own video in the same manner as everyone else's videos, others will only show it at a very small size, or sometimes not at all. When signing, it's important to have an idea of the amount of visible space around you that's available for signing. Otherwise, you could end up signing off-screen where nobody can see.

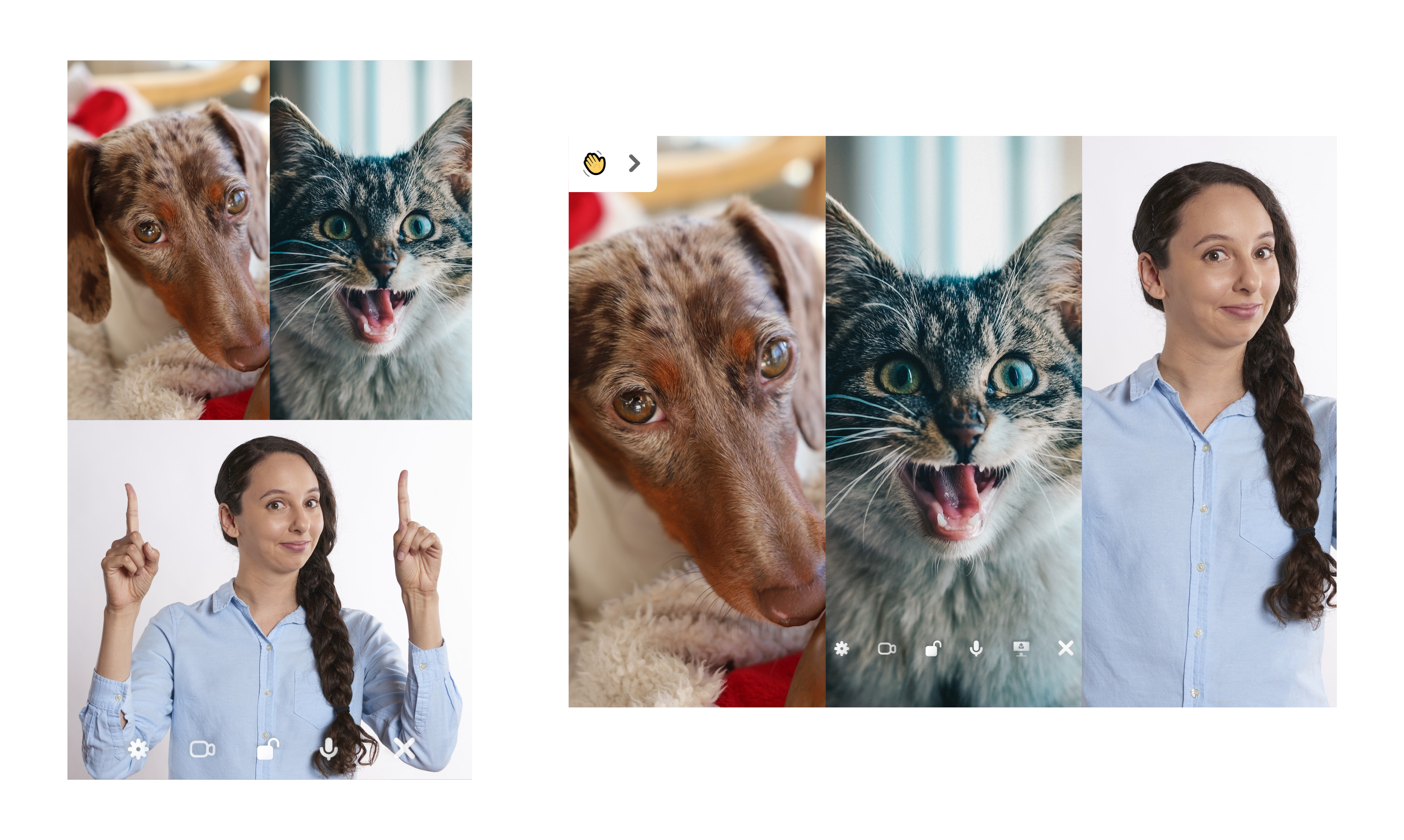

Videos cropped differently

Even if you can see your own video and think you're using your space correctly, it may not be enough: video meeting apps will generally crop videos to lay out nicely. In some cases, the crop varies depending on the type of device it's displayed on. This means that how someone sees themselves on their own device does not necessarily match what is shown to anyone else in the video chat.

This can have a huge impact on signing. If someone sees themselves on video with plenty of room around them, they would think they have all that room to use for signing. In actuality, their video could be cropped so much that only their face is visible, hiding their signing from others in the video chat.

Lack of good captions

Some video chat apps don't have a captioning feature at all. Many do now have captioning, but the quality can vary. Some apps will allow manual captioning, which is generally more accurate (and costly) than automatic captioning. Captions are beneficial for DHH observing a speaking presenter. In some cases, an interpreter would be more beneficial, especially if there is 2-way communication.

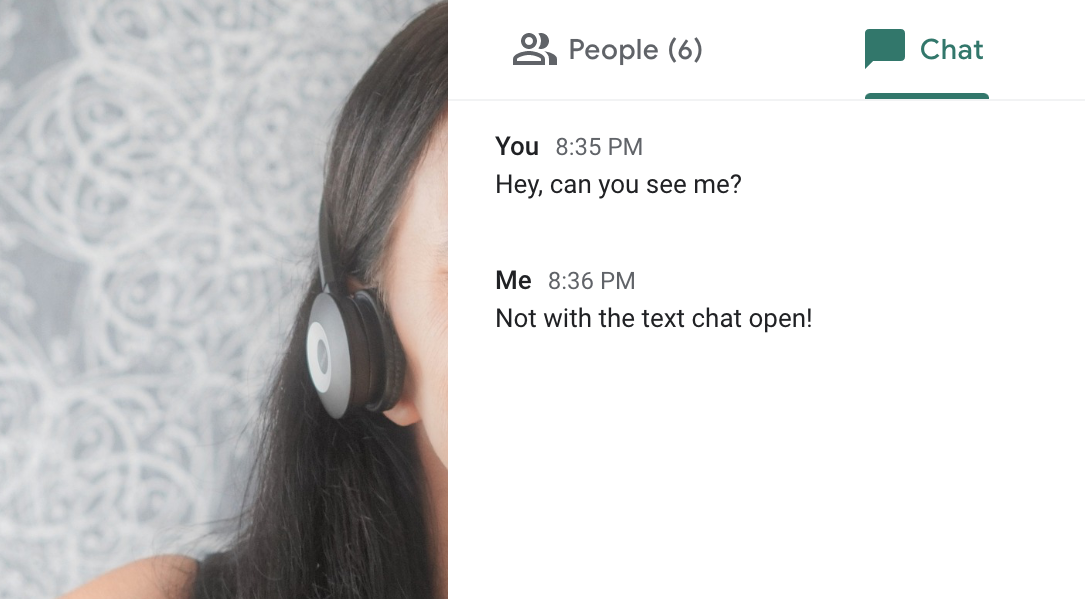

Text chat interface obstructs video

Pretty much all video chat applications also have a basic text chat feature participants can use to converse through text-based messages. This can be handy for sharing links, troubleshooting audio/video issues, and having side conversations. It's one of the tools DHH can use to communicate with the hearing. In our ASL practice meetup, it's also been useful for explaining things when we are unable to get something across using sign language.

Unfortunately, in many cases the text chat interface obstructs videos when in use. This makes it difficult or even impossible to see someone's reaction to messages. This kind of visual feedback can be critical to know if someone is understanding, responding to, or even seeing a message.

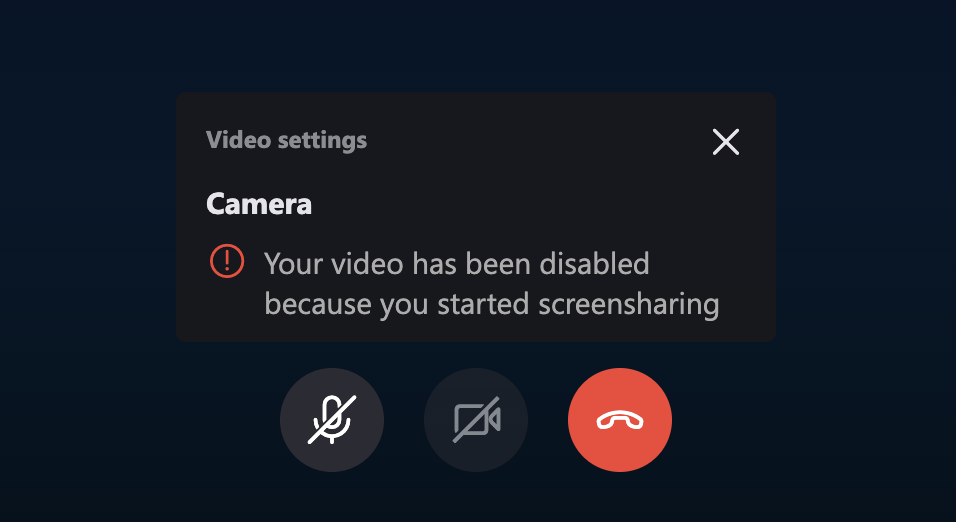

Screensharing disables video

In some video chat apps, when someone shares their screen, their camera is forced to be disabled. That means nobody in the video meeting can see the presenter. In some cases, the shared screen will take over the whole video meeting so it's impossible to see anyone's video.

This design assumes that the presenter is speaking, and the audience is hearing.

What if the presenter were DHH? The presenter cannot sign, since their camera is disabled. If there is an interpreter for a hearing audience, the interpreter would need to physically be with the presenter. The presenter may be able to communicate to their audience via text chat, but that means the presenter will have to go back and forth between their shared screen and the text chat.

What if the audience were DHH? The audience would not be able to lip-read or see the presenter signing, since the presenter's camera has been disabled. If everyone's cameras have been disabled, including an interpreter's, they would not be able to lip-read or see them signing either. If the presenter is speaking, captions may be helpful.