Critical Perspectives in Public Health Feminisms

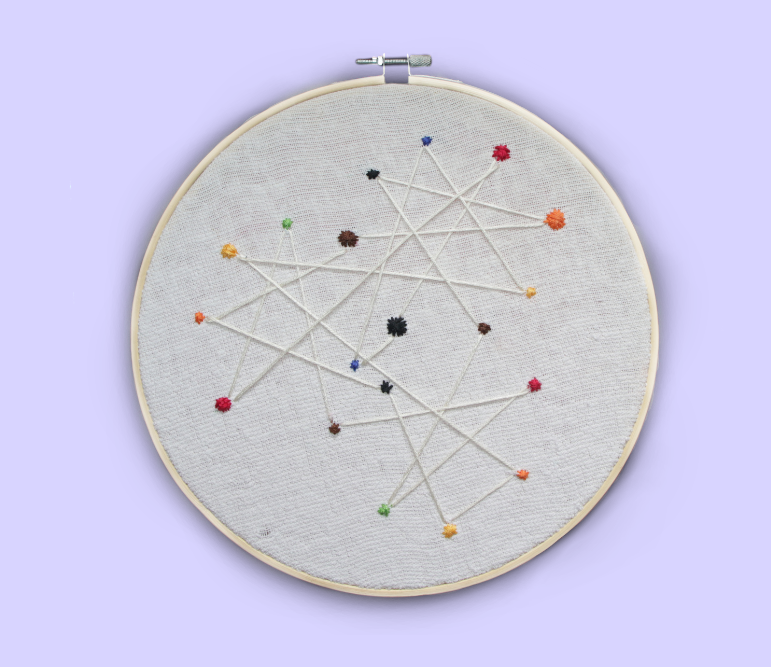

Embroidery hoop art for a book cover.

Details

Links

Introduction

I created this embroidery hoop art for an assignment in Dr. Renée Monchalin's inaugural Public Health Feminisms course at the University of Victoria (UVic).

It is now featured on the cover of her edited collection, Critical Perspectives in Public Health Feminisms, and will be used as a textbook in university courses.

The book includes a more detailed description of the artwork, but I will share some highlights here.

Embroidery

The medium of this piece, embroidery, was chosen with intention. While the assignment was an “art” project, I deliberately chose a medium that is typically considered a “craft”. I did this as an act of rejection of the art/craft hierarchy.

The art/craft hierarchy suggests that there is a distinction between arts and crafts, and that crafts are less artistically significant than arts. In fact, the real difference between the two is not material, skill, or purpose, but rather where they are made (i.e. at home, at work) and who tends to make them (i.e. women and lower-class, men and upper-class). Much like the patriarchy, the art/craft hierarchy is a construct rooted in sexist and capitalist values. By submitting a “craft” as “art”, I purposefully chose to conflate the two, thereby renouncing the art/craft hierarchy.

Embroidery is often thought of as “women’s work”, and considered “light and easy”. In fact, embroidery, like much of “women’s work”, particularly care work, is incredibly labour-intensive, time-consuming, and underappreciated. Indeed, the relatively simple piece I created for this project took several hours to complete.

Embroidery has a long relationship with politics, power, and resistance. In some cultures and times, embroidery marked a girl’s path into womanhood and kept them from actively participating in politics. Despite this, women have used embroidery for communication when they otherwise would not be able to, creating journals, propaganda, and more.

Design

While the resulting piece is visually quite simple, it represents significantly more complex ideas. I incorporated many of the topics explored throughout the course, including: intersectionality, knowledge-sharing, reciprocity, social determinants of health (SDOH), and feminism.

The colours represent diverse populations, and also recognize some of the groups who continue to be disproportionately affected by negative health outcomes.

The sizes of the coloured dots vary to represent variations in power, including SDOH such as gender, race, disability, and income.

The dots are arranged to loosely form 3 overlapping circles. These circles represent different types of groups, such as: communities, sectors, generations, and identities. When the circles are viewed as identities, the intersections represent intersectionality, acknowledging that individuals experience unique oppressions based on the sum of their identities

A light beige thread forms connections between the dots both within and between their circles. This represents communities, sectors, and generations working together and sharing knowledge which is necessary for improving population health.